Low fishing quotas are the most effective measure for saving the Baltic Sea’s fish populations. But when there is a lack of political will to reduce quotas, fishing bans become an important tool. However, these bans are often implemented at the wrong time and therefore have no effect. If Sweden wants to make a difference, the government must push for fishing bans that actually work – and continue to fight for low quotas.

In the context of the annual EU negotiations on fishing quotas, Member States in the Council of Ministers can propose joint measures to support the recovery of fish stocks in the Baltic Sea. For example, during the 2024 negotiations on Baltic Sea quotas, the Council decided to ban trawling for herring and sprat during the period when these populations were assumed to be spawning in 2025.

The ban — or the so-called spawning closure — took place between May and August and covered the entire central Baltic Sea in areas beyond 12 nautical miles from the coast. However, during this period, there is hardly any large-scale fishing activity, a fact confirmed by vessel data obtained by BalticWaters from the Swedish Maritime Administration.* In practice, such a ban is therefore ineffective.

In a recently published report commissioned by the European Parliament, researcher Christian Möllmann from the University of Hamburg, concludes that the situation for fish stocks in the Baltic Sea is critical and that strong measures are needed to restore and maintain the populations at sustainable levels. Properly timed and well-designed fishing bans are a step in the right direction.

Temporary fishing bans are better than none

Knowledge about the effects of spawning closures remains limited. At the same time, research indicates that such closures can have certain positive effects – for instance, by allowing more and larger fish to contribute to the reproduction of a stock. Fully protected areas, however, are more effective in promoting recovery. Yet, if fully protected areas cannot be established for various reasons, well-timed and well-designed spawning closures are still better than having none at all.

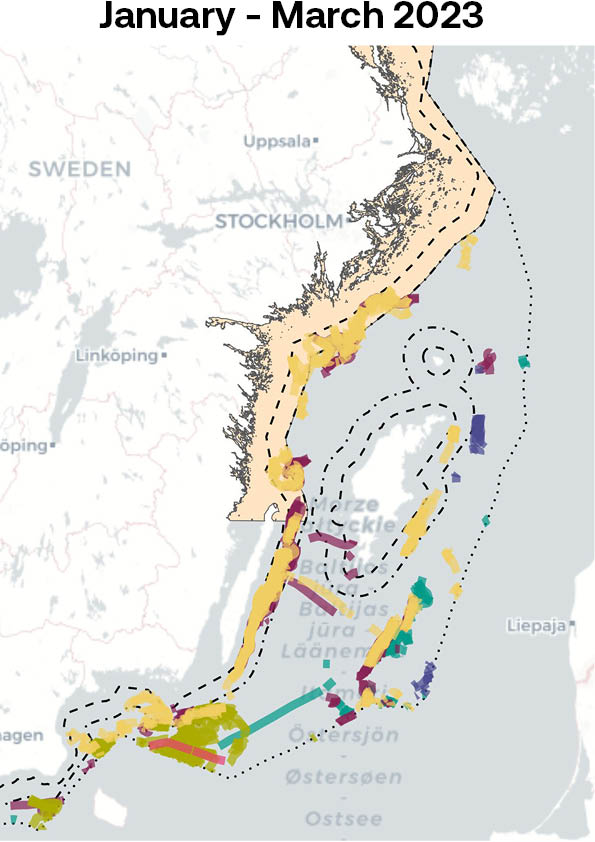

Data from 2023 obtained by BalticWaters from the Swedish Maritime Administration shows where trawlers over 24 metres operated during different periods of the year. The data reveals that these vessels were significantly more active between January and March than between April and August. A fishing ban aimed at protecting fish populations should therefore be implemented during the first months of the year to be effective. The maps below illustrate parts of the central Baltic Sea.

Earlier closures could yield better results

Ahead of this year’s EU negotiations on Baltic Sea fishing quotas, taking place on 27–28 October, the European Commission has proposed once again introducing spawning closures for herring and sprat in 2026. In this context, the Swedish government has an important role to play: to advocate for closures to be implemented at the beginning of the spawning season, between January and March, rather than at the end. The closures should remain in place for as long as science deems necessary to allow fish populations to recover.

Another reason to place a fishing ban during the first months of the year is that most herring stocks are located outside the immediate coastal zone in winter, and are therefore exposed to large-scale trawling activity.

The Swedish government holds a unique position to persuade other countries

As chair of the regional fisheries forum for the Baltic Sea, BALTFISH, Sweden has a unique opportunity to take leadership on this issue. The government should use this position to push both for low quotas and for fishing bans that actually make a difference.

Sweden can also request that the European Commission mandate the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) to produce scientific advice comparing the effects of spawning closures implemented during different periods. Such an analysis would provide the government with strong arguments in discussions with other countries and help ensure that decisions are based on the best available knowledge.

As with the issue of fishing quota levels, decisions on the geographical and temporal placement of closures lie entirely with the Member States. No one else can meaningfully act in the matter. The Swedish government therefore cannot afford to remain passive – it must actively advocate for both low quotas and well-timed closures if the Baltic Sea’s fish stocks will have a chance to recover.

The brief in short

Ahead of the upcoming EU negotiations on next year’s fishing quotas in the Baltic Sea, the Swedish government should, in addition to advocating for low quotas in line with the European Commission’s proposal, work to ensure that the proposed fishing bans are placed during the first months of the year. This would likely have a greater impact than implementing them later in the year. In 2025, Sweden holds the chairmanship of BALTFISH – a unique opportunity to influence other countries on this issue.

*The vessel data from 2023 obtained by BalticWaters from the Swedish Maritime Administration shows where trawling vessels have operated within the Swedish Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the Baltic Sea. Based on selected criteria, trawled tracks have been identified and mapped. The criteria applied are: (1) the vessel’s speed remains relatively constant between 1.25 and 5.5 knots (1.5 and 5.5 knots for vessels over 40 metres), and (2) the speed remains relatively constant for at least 24 minutes.

Inlägget Baltic Sea Brief 80: The Baltic Sea needs real measures – not symbolic bans dök först upp på BalticWaters.